On this date, March 31, 1968, US President Lyndon Johnson appeared on live television to make the announcement that he was partially stopping the American bombing of Vietnam and that he would not run for president in his party.

“There is division in the American house now,” Lyndon Johnson declared.

Most observers were taken aback when President Lyndon Johnson declared that he would not run and acknowledged the “division in the American house” over the Vietnam War and domestic unrest.

He said, “I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office, the Presidency of your country, with American sons in the field far away, with the American future under challenge right here at home, with our hopes and the world’s hopes for peace in the balance every day.

I shall not seek and I will not accept the nomination of my party as your President

– President Lyndon Johnson

The electorate was in astonishment and elation when it was revealed that president Lyndon Johnson had decided not to run for re-election. The nature of the conflicts that had so severely divided the nation along ideological, racial, and class lines was crystallized at the same time as he withdrew from the contest. But within a few days, it became painfully clear that no amount of political sacrifice could heal the nation’s divides. Johnson’s administration served as both a representation and a symbol of the nation’s divisions, but it was not the primary cause of them.

“With America’s sons in the fields far away, with America’s future under challenge right here at home, with our hopes and the world’s hopes for peace in the balance every day,” Johnson said in his unexpected announcement, “I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office—the Presidency of your country.”

On some fundamental level, his decision not to run again reflected his acceptance of political fact. Lyndon Johnson had turned into the symbol of America’s divides despite all of his legislative successes (the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Medicare, and Medicaid). Those on the Right believed Johnson had overburdened the system with big-government initiatives that infringed on people’s freedoms. A large portion of the Left saw Johnson as the dishonest wheeler-dealer who had deceived America into entering the deadly, gory Vietnam War.

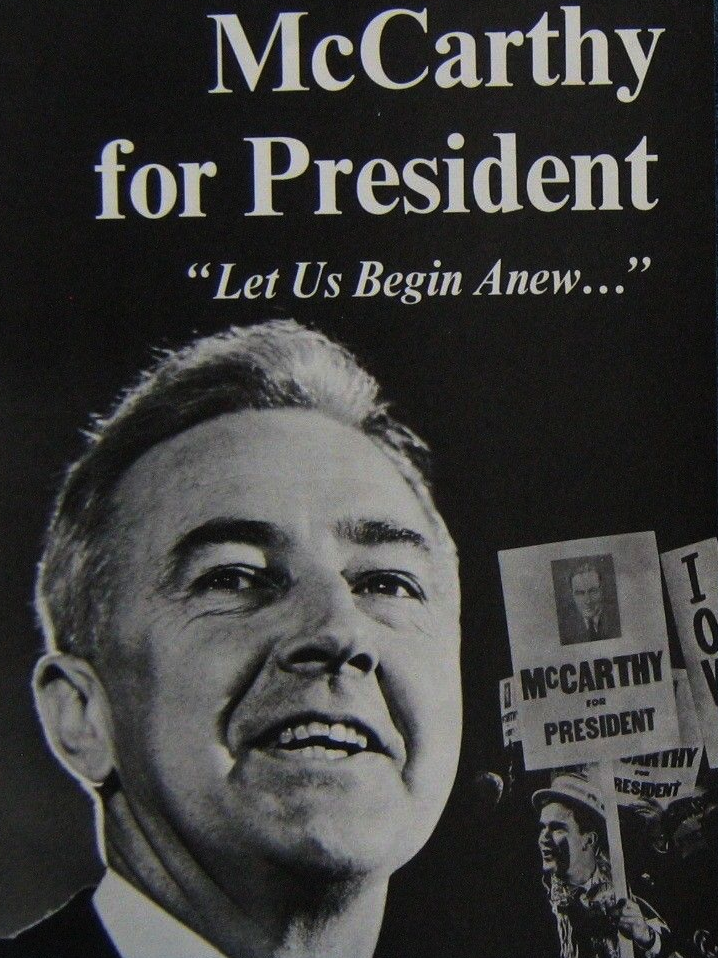

In November, Lyndon Johnson confronted steep odds; his top advisors worried that he might not even secure the nomination for reelection. Sen. Eugene McCarthy, an antiwar candidate, mounted a surprisingly strong primary campaign against LBJ in New Hampshire on March 12. With his public approval rating hovering around 36%, McCarthy received 42 percent of the vote to LBJ’s 48 percent. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy of New York, LBJ’s longtime foe, announced on March 16 that he would also run against Johnson for the election four days later.

Rarely do presidents decline to run for a complete second term. However, Lyndon Johnson’s management of the Vietnam War lingered over his White House like an albatross. He had lied about American military advancement numerous times, and the Tet Offensive, in which Viet Cong forces attacked important South Vietnamese cities in January, disproved the administration’s expectation that victory was imminent. (Harry Truman, similarly saddled with the unpopular Korean War, refused to run in 1952.)

If Johnson had run for reelection, Richard Nixon, the top Republican candidate, might have defeated Johnson in the general election. Republicans looked to be ahead in the race to retake the White House as Johnson’s withdrawal caused turbulence within the Democratic Party.

The fact that LBJ’s statement was so unexpected contributed to its dramatic nature. Even LBJ himself wasn’t sure he would say the things his aides had written for him when he took the stage to give the address. LBJ had built a reputation as a brilliant legislative operator, a master manipulator of men and laws, and a politician who wanted to both advance his own self-interest and outdo FDR as the greatest reform president of the 20th century. This reputation was rooted in decades of service in Senate leadership and then in the White House.

However, by March 1968, “Landslide Lyndon,” who earned the moniker after defeating Coke Stevenson in the 1948 senate primary, was overcome with fear, insecurity, and doubt due to the war, inner-city riots, and the perceived failure of the war on poverty.

McCarthy and Kennedy, the two serious Democratic primary rivals already in the running, as well as their advisors and allies, reacted to Johnson’s unexpected decision to not run against them with a mixture of jubilant joy and unsettled uncertainty about what his departure would mean for their chances of winning the presidency. Jim Whittaker, a friend of RFK’s, called Kennedy after hearing Johnson make his statement and wished him well, as though the candidate had just won the nomination.

ALSO READ: Robert Kennedy, The Great President America Lost in 1968

McCarthy credited antiwar activists in general and those who had worked on his campaign in particular for Johnson’s decision to drop out of the race. McCarthy said, “I don’t think they could stand up against five million college kids just shouting for peace.” McCarthy was speaking of Johnson’s supporters. There was excessive willpower present.

When Lyndon Johnson announced that he would depart the White House in January, Richard Goodwin, a former LBJ speechwriter who had joined McCarthy’s campaign to oppose the Vietnam War, felt “stunned, then exultant.” Goodwin jumped up from his chair, walked over to the TV, and gestured at Johnson. He said, “I figured it would take another six weeks.

READ: Remembering 1968

But Lyndon Johnson’s resignation also brought up some challenging issues for Democrats. Johnson’s choice alarmed the candidates and their supporters because they thought it might dampen the enthusiasm that had fueled their political success and excitement from the moment they declared their primary challenges. Antiwar activists were ecstatic as Democratic officials scrambled to come up with a response to Johnson’s abrupt withdrawal.

[…] The Greatest Surprise Of The Century, Lyndon Johnson Quits […]