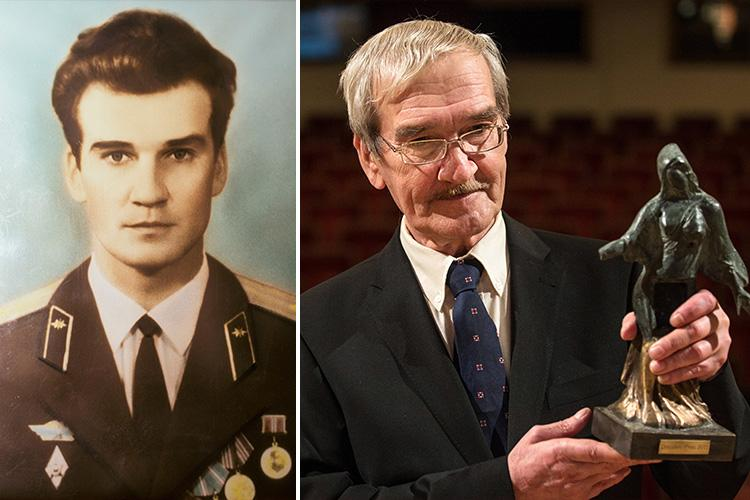

Stanislav Petrov was Born in Russia, in September 1939. He was a lieutenant Colonel of the Soviet Air Defence Forces. The little-known Russian whose decision averted a potential nuclear war died on May 19, 2017.

Petrov enrolled at the Kyiv Military Aviation Engineering Academy of the Soviet Air Forces, and after graduating in 1972 he joined the Soviet Air Defence Forces. In the early 1970s, he was assigned to the organization that oversaw the new early warning system intended to detect ballistic missile attacks from NATO countries.

How did Stanislav Petrov save the world?

It was early morning of September 26, 1983, the day when Stanislav Petrov helped prevent the outbreak of a nuclear war.

The 44-year-old lieutenant colonel of the Soviet Air Defence Forces was a few hours into his shift as the duty officer at Serpukhow-15, the secret command center outside Moscow, where the Soviet military monitored its early-warning schedules over the United States, anytime alarms went off.

The Computers eventually warned that five Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missiles had been launched from an American base.

The alarm sounded during one of the tensest periods in the Cold War. Three weeks earlier, the Soviets had shot down a Korean Air Lines commercial flight after it crossed into Soviet airspace, killing all 269 people on board, including a congressman from Georgia. President Ronald Reagan had rejected calls for freezing the arms race, declaring the Soviet Union an “evil empire.” The Soviet leader, Yuri V. Andropov, was obsessed with fears of an American attack.

The decision-making chain was solemnly in the hands of Stanislav Petrov.

His superiors at the warning-system headquarters reported to the general staff of the Soviet military, which would consult with Mr. Andropov on launching a retaliatory attack.

After five nerve-racking minutes — electronic maps and screens were flashing as he held a phone in one hand and an intercom in the other, trying to absorb streams of incoming information — Colonel Petrov decided that the launch reports were probably a false alarm.

“There was no rule about how long we were allowed to think before we reported a strike,” he told the BBC. “But we knew that every second of procrastination took away valuable time, that the Soviet Union’s military and political leadership needed to be informed without delay. All I had to do was to reach for the phone; to raise the direct line to our top commanders — but I couldn’t move. I felt like I was sitting on a hot frying pan.”

Despite the tension engulfed in the command center, with as many heads as 100 relying on Petrov’s decision, he opted to report the alarm as a system malfunction and still reinstated not to regret his decision.

“I had a funny feeling in my gut,” he told The Washington Post. “I didn’t want to make a mistake. I made a decision, and that was it.”

Colonel Petrov was at first praised for his calm, but in an investigation that followed, he was asked why he had failed to record everything in his logbook. “Because I had a phone in one hand and the intercom in the other, and I don’t have a third hand,” he replied.

The false alarm was apparently set off when the satellite mistook the sun’s reflection off the tops of clouds for a missile launch. The computer program that was supposed to filter out such information had to be rewritten.

Colonel Petrov said the system had been rushed into service in response to the United States’ introduction of a similar system. He said he knew it was not 100 percent reliable. “We are wiser than the computers,” he said in a 2010 interview with the German magazine Der Spiegel. “We created them.”

In a later interview, Petrov stated that the famous red button was never made operational, as military psychologists did not want to put the decision about a nuclear war into the hands of one single person.

The incident became known publicly in 1998 upon the publication of Votintsev’s memoirs. Widespread media reports since then have increased public awareness of Petrov’s actions.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/61550601/GettyImages_50803740.0.jpg)

There is some confusion as to precisely what Petrov’s military role was in this incident. Petrov, as an individual, was not in a position where he could have single-handedly launched any of the Soviet missile arsenals. His sole duty was to monitor satellite surveillance equipment and report missile attack warnings up the chain of command; top Soviet leadership would have decided whether to launch a retaliatory attack against the West. But Petrov’s role was crucial in providing information to make that decision.

According to Bruce G. Blair, a Cold War nuclear strategies expert, and nuclear disarmament advocate, formerly with the Center for Defense Information, “The top leadership, given only a couple of minutes to decide, told that an attack had been launched, would make a decision to retaliate.” In contrast, nuclear security scholar Pavel Podvig argues that, while Petrov did the right thing, “there were at least three assessment and decision-making layers above the command center of the army that operated the satellites”, so Petrov’s report would not have directly impacted on decision-making.

Colonel Petrov retired from the military in 1984. He got a job as a senior engineer at the research institute that had created the early-warning system but retired to care for his wife, Raisa, who had cancer. She died in 1997.

Stanislav Petrov’s life after saving the world.

Colonel Petrov had largely faded into obscurity — at one point he had been reduced to growing potatoes to feed himself — when his role in averting nuclear Armageddon came to light in 1998 with the publication of the memoir of Gen. Yuriy V. Votintsev, the retired commander of Soviet missile defense.

Read: Stanislav Petrov, Soviet Officer Who Helped Avert Nuclear War, Is Dead at 77

The book brought Colonel Petrov a measure of prominence. In 2006, he traveled to the United States to receive an award from the Association of World Citizens, and in 2013 he was awarded the Dresden Peace Prize. He was the subject of a 2014 hybrid documentary drama, “The Man Who Saved the World.”

Jakob Staberg, the producer of the film, said in a phone interview on Monday that he had tried to contact Colonel Petrov by phone and email for the last several weeks, hoping to discuss the film’s Russia release, scheduled for February. He said he had not thought much of the delay because Colonel Petrov often traveled.

Colonel Petrov’s role in the film brought him into contact with American celebrities like the actors Kevin Costner and Robert De Niro, but he did not embrace the spotlight. “I was just at the right place at the right time,” he says in the film.

Recognitions, Honours, and Awards.

On 21 May 2004, the San Francisco-based Association of World Citizens gave Petrov its World Citizen Award along with a trophy and $1,000 “in recognition of the part he played in averting a catastrophe.” In January 2006, Petrov traveled to the United States where he was honored in a meeting at the United Nations in New York City. There the Association of World Citizens presented Petrov with a second special World Citizen Award. The next day, Petrov met American journalist Walter Cronkite at his CBS office in New York City.

That interview, in addition to other highlights of Petrov’s trip to the United States, was filmed for The Man Who Saved the World, a narrative feature and documentary film, directed by Peter Anthony of Denmark. It premiered in October 2014 at the Woodstock Film Festival in Woodstock, New York, winning “Honorable Mention: Audience Award Winner for Best Narrative Feature” and “Honorable Mention: James Lyons Award for Best Editing of a Narrative Feature.”

Read: Robert Kennedy, The Great President America Lost in 1968

For his actions in averting a potential nuclear war in 1983, Petrov was awarded the Dresden Peace Prize in Dresden, Germany, on 17 February 2013. The award included €25,000. On 24 February 2012, he was given the 2011 German Media Award, presented to him at a ceremony in Baden-Baden, Germany.

On 26 September 2018, he was posthumously honored in New York with the $50,000 Future of Life Award. At a ceremony at the Museum of Mathematics in New York, former United Nations.

However, Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov never managed to win the Nobel Peace Prize.